If a time traveller journeyed through time and told us that a 2D Metroidvania title would be one of the best games Double Fine ever released, we'd both scoff in disbelief and question why said time lord didn't tell us something more important, like who wins the US Election – or whether Paul Blart: Mall Cop 3 is ever made.

See, on paper, Headlander should just be one of those games that we get every month on PlayStation Plus that nobody plays and everyone complains about – but it's just so well done. The term Metroidvania is tossed around aplenty, but this game feels like a true successor that's worthy of the description. The floating space station environment feels truly open, with nooks and crannies, secret areas, hidden jokes, and Easter eggs everywhere, and the map isn't just full of places that you can go back to – rather places that you want to go back to.

In Headlander, you play as a floating, disembodied head that's able to fly around and use its vacuum to attach itself to bodies and machines. Since humanity has transferred its consciousnesses to robots and a mysterious component called the Omega Gem has been put inside every human's head to suppress their thoughts and emotions, you can quite easily pull their noggins off and plonk yourself on their body, effectively gaining control of it. This has plenty of practical applications, like taking control of the antagonist Methuselah's armed police force, named Shepards, or mapping robots, named Mappys, in order to download their location data.

Thanks to this mechanic, the game gets a lot more interesting and open than your usual 2D sidescroller. The aforementioned space station that you explore has many different colour-coded doors – operated by an AI called ROOD, because what Double Fine game doesn't have a snarky robot? – that go from red to indigo, and demand that your body has the same colour or better to pass through. This makes for some great exploring, and really encourages you to scour all areas of the map to look for different coloured bodies and doors in order to progress or find secrets.

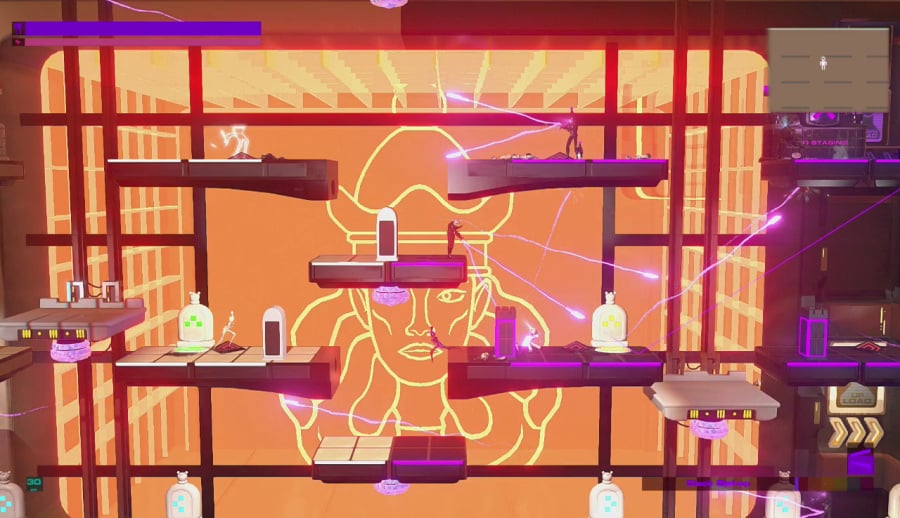

There's also quite a surprising amount of gunplay in Headlander, but it feels tweaked to perfection. Different bodies that you take have different weapons – some have single shot rifles, others can shoot four lasers at a time, and you can even take control of spider walkers near the end of the story – encourage you to switch bodies mid-combat in order to get tactical advantages, and there's even a basic cover system to switch things up. Neon lasers often fill the screen in a spectacular shower of lights, and while it's sometimes hard to pick out where you are during the action, you can't deny that it looks beautiful.

The same could be said about the entire release. While it does have that typical cartoony Double Fine style, the 70's sci-fi, retro-futuristic aesthetic is unique and interesting; the psychedelic light show that occurs when you die and respawn, the occasional screen static, and the saturated block colours all work to set the tone of Headlander.

Yet, as the game goes on, the story and tone seems to get darker and darker, morphing from a corny sci-fi TV show to something of an Orwellian dystopia. There are little audio hints that suggest something isn't quite right – talking to the many hippy-like residents of the space station shows underlying issues, and the passive-aggressive, Big Brother-like presence of Methuselah's voice over the intercom feels threatening. But even though the release does well at telling this darker story, it still manages to keep the studio's trademark humour going, from the evil Mappys that seek revenge near the end of the game to the comedic comments of Earl – your guide who talks you through most of your adventure.

Not only does the story develop as the game goes on, but the gameplay gets more interesting and complex, too. Many secret passageways and air ducts lead to upgrade stations that can upgrade your helmet's health, thrust, or power, while there are energy stations that you can harvest to attain upgrade points, which you can then use to buy enhancements or new moves. There are plenty of new abilities to unlock, from being able to vacuum heads and drop them like bombs to converting used bodies into sentry turrets.

But what Double Fine perhaps does best in Headlander is balance the gameplay between head and body. Most of the time, you need to have a body to progress through different rooms and fight off enemy Shepards, but you'll always need to detach eventually, whether it's to progress through the game to find secrets, to switch to a more powerful body, or simply because your current form's about to be destroyed – there isn't a better feeling than jetting off from your body just as it explodes.

Headlander is so well-produced, so innovative, and so mind-bogglingly fun that the only thing it can really be faulted for is its technical failures. While there are virtually no loading times in the game whatsoever – even respawning only takes a few seconds – there are some issues with framerate drops towards the end, when the lasers storm onto the screen and the title just can't seem to take it.

Conclusion

It's a testament to the excellence of Headlander that it can only be faulted for its slight technical flaws. Everything about it is so finely tuned, from its gunplay to its platforming to its puzzles, and it doesn't just stay true to classic Metroidvanias – it also builds upon the foundations that they laid. The story is well told, the characters are entertaining, the environments are fleshed out, and the humour is as brilliant as always. Headlander's one of the best games that Double Fine has ever produced.

Comments 11

Nice one, to be honest this wasn't on my radar and even looking at the screenshots it looks generic as hell but I'll be giving it a go now.

Sounds fantastic, as always I'll await a sale, but I really look forward to playing this one. Great review.

How much is it?

I DONT CARE!! JUST TAKE MY MONEY!!!!!

@kyleforrester87 I didn't know about this game until a few weeks ago, and now I'm glad I do! I wasn't excited for it either, but Double Fine knocked it out of the park with this one.

@LieutenantFatman Thanks! It's £15, and the campaign took me about 10 hours to complete, so relatively good value.

@fabisputza00 £15, so not a bad price for a GOTY contender

Great review Sam. But is it as good as Fez or Axiom Verge?

@themcnoisy I can't compare it to Axiom Verge as I've never played it, but I'd say it's a tad inferior to Fez. It's easily a Double Fine classic, I'll say

I watched the PSN trailer for this game and it immediately reminded me of an old Sean Connery 70's sci-fi movie called Zardoz.

Watch the trailer on YouTube...

Had to get it, love Metroidvania games and thankfully a lot more of them seem to be around at the moment. I'll get stuck into this when I've finished Song of The Deep - which is another excellent Metroidvania!

Loving this!!! Like a cross between Super Metroid and Steamworld Heist!! Played for 3 hours THEN - a damn gamebreaking bug!!!! When ur turning off the 3 coloured lift shields, if you stop playing without completing the task, u end up in a closed off section under a lift that can only be controlled by your head ... ie you cant get to it because its connected to the platform above!! Don't know why the lift went back up to that floor. think I mustve activated it then boosted the head off and flew underneath while it was going up!! Nightmare though!! Started again, still loving it!!!

This game has a lot of personality, humor, style and a twist (being alble to put your head on any body, robots, robotic dogs, computers and gain their abilities) on the metroidvania style game play. I'd also compare the game play to the more recent game, Shadow Complex. The 60's/Blade Runner soundtrack is great too. It's a real pleasure to play this game and one of the best games of the year. A real surprise from the usual typical games we get every year. Buy it!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfUNzmdR2TM

Really liked this game but it started to wear thin by the end. Problem is the power ups are largely ignorable. Once you can tug a robots head off theres little need to use the blaster power ups, bomb, thrust etc. I found everything and fully levelled up BUT I didn't feel at all more powerful towards the end. Since the way you progress is through colours of identical droids, the power ups play a less important role. Its not like metroid where you get a cool new tool/weapon to progress. You just change from one robot to another. Good game, maybe an 8 for me!

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...