We were something like six hours into Vane when we glanced down at our phone to see what time it was, and realised that we'd only been playing the game for forty-two minutes. How was this even possible? It was like when Matthew McConaughey visited Dr. Miller's Planet in Interstellar: a world catastrophically affected by the intense gravity of a nearby black hole that slows down time so much that standing on the surface for ten minutes accounts for seven years passing back on Earth. It was that, but in reverse. Mere minutes had gone by in what felt like hours. On the plus side, that meant that this author's tea was nearly ready, and Lauren was doing risotto.

The downside, of course, is that Vane is such a chore to play that everything feels like it takes way longer than it needs to. There's a bunch of problems here, but even if the technical and mechanical issues that plague the game were to magically go away thanks to post-release patches, the central crux of the experience would still be flawed.

You begin Vane as a young boy trying to find shelter during a spectacular storm that features lightning strikes, furious winds, tiles being ripped from buildings, and an ice cool synth soundtrack. It's an engaging opening that hints at narrative delights that sadly never materialise, and once the winds have died down, you're inexplicably playing as a bird and everything goes to pot.

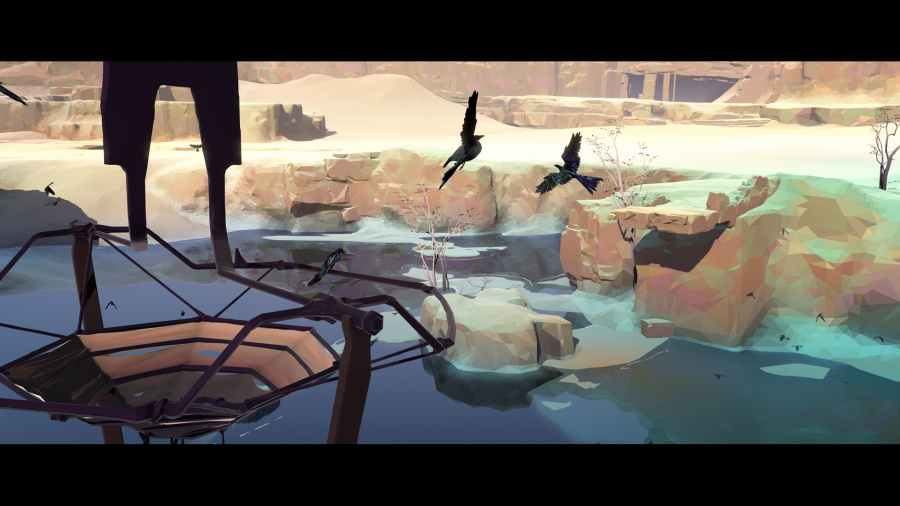

You're a crow. Perhaps a raven, or jackdaw, or rook. Who knows? Maybe you can Google it during one of the many times you happen upon a game-breaking bug that requires you to restart. Either way, you fly about in the skies high above a sizeable chunk of desert, and... well, that's up to you. There's no hints, there's no quests, there's no clues, there's no waypoints. There's not even the vaguest of intimations as to what you should be doing. The game is frustrating not because the joy of exploration is lost on us, or that we're simply too thick to play a game that doesn't spoon-feed us or hold our hands. It's that what you're supposed to do here is often so obtuse that you'll discover the solutions to puzzles that you didn't even know were puzzles by luck more often than judgement.

The desert section of the game, for example, features a puzzle in which you must transform back into your child self by standing in some golden dust. The golden dust is trapped in a ball. The ball is trapped in a cage hanging from a vane. There are numerous smaller vanes around the desert with birds hovering above them. You have to fly to one of these smaller vanes, land on it, and hit triangle to instruct your bird brothers and sisters to fly to the big vane. Once you've done that four or five times around the desert, you need to fly to the big vane, land on it, hit triangle to instruct your bird brothers and sisters to land on it with you, all so that the combined weight of the birds collapses the structure, the cage cracks, the ball falls, and you're free to stand in the golden dust and be a boy again.

But there's no logical reason that you'd ever come to those conclusions on your own without just doing mad things for the sake of it. You don't know you need to be a boy to progress. You don't know that standing in golden dust turns you back into a boy. You probably haven't seen that the ball in the cage is full of golden dust. Pressing triangle when standing on the big vane makes birds land next to you whereas if you press it when you're on the smaller ones it makes them fly away. This isn't so much a puzzle as it is as an arbitrary list of things you need to do in order to move on to the next area.

The slam dunk comes when you're finally a boy again, and you (again) have absolutely no idea how to progress. Without going into too much detail, it involves walking up to a locked door and jumping through it, magically finding yourself on the other side, which means that the boy you're playing as either has the power to pass through very specific surfaces in very specific locations and only if he jumps, or that the game glitched and the door was supposed to be open. Honestly, we've got no idea on that one, and we're not going to reload the checkpoint to find out because reloading the checkpoint begins the entire desert section again.

There's nothing wrong with a game asking you to figure things out for yourself, or one without an HUD to point out items of interest, but there has to be environmental storytelling in place to teach the player gameplay mechanics organically that they can then use to progress on their own terms. At times it seems like Vane expects you to be clairvoyant.

Thankfully, once you're out of the expansive desert section of the game everything does become a little more streamlined and logical, but a new set of problems quickly arises. The bird doesn't control particularly well, the camera clumsily finds itself in the wrong place at the wrong time so frequently that you'd be forgiven for thinking it was actually designed to be unhelpful, and the enclosed spaces of the caverns that you find yourself in simply exacerbate both of these issues exponentially.

When you're playing as the boy the controls are slow and clunky, and he trundles around the environment with all the grace and finesse of Barney the Dinosaur trying to run through a swimming pool filled with treacle. Occasionally, the boy will just stop moving, or he'll fall to his knees and stay there for five seconds or so. Perhaps he can sense our will to live ebbing away. It's tedious.

Conclusion

Vane is exhausting, ponderous, bewildering, endlessly frustrating, needlessly obtuse, narratively unsatisfying, mechanically clumsy, and technically shoddy, all shot through a camera so ill-equipped to deal with the rudimentary task of showing you what's happening on screen that you might as well pop a blindfold on and try using The Force.

Comments 20

pops on a blindfold and attempts to do the Force

I CAN DO IT

I CAN DO IT

I CAN DANG DO THIS!

That's gotta be a contender for best opening paragraph in a review.

A shame that this is a flop though.

Obscure Queens of the Stone Age B-side for the tag line?

You win the internet for the week.

@Its_badW0lf it was in reference to the Carly Simon song from the '70s. I'd hate to accept the winning the Internet prize disingenuously.

In today’s world, where games with 10 hours of good content are stretched into 100 hour “open world adventures”, one should be grateful for a game that basically offers “hours of fun” within a few minutes.

Its middling reception makes me sad. I hoped they could improve it after the really bad PSX 2017 demo, but I guess not.

@johncalmc still made my week mate, and the write up is excellent to boot

That really seemed like it was on pace for a 1 or a 2. The score of 4 had me in awe!

That first paragraph is gold. John should write all the reviews.

Ah yes, Interstellar! That film that seemed to last an eternity in the seventh circle of Hell yet only had a running time of 150 minutes or so.

Still interested in this game though

I’m glad it wasn’t just me then!!

I was really looking forward to this but jeezo what a chore it’s been.

I loved Interstellar though!!

Excellent review. At least I think it was, I don't know. Because all I can think about is Barney the Dinosaur struggling to get through that treacle-filled swimming pool, his little arms flailing as he slowly sinks.

And this is what happens when we excited over games with the good graphics and nothing more, and is this reason why I'm always so skeptical when it comes to indies, anime games, and china developed games.

First Entwined, then Toren, then Koi, then Oure, now this. Let this game serve a lesson to us that just because an upcoming game looks pretty or stylish, that doesn't mean the end results will be good. Thankfully though, on the dev's reddit AMMA, they're working on fixing the game's issues like the save system, bugs, controls and camera, meaning that not all is lost. So if you have issues with the game, go to their AMA page and post your opinion on the game (don't be too harsh though).

Still, never forget.

I've played about 3 hours of Vane. The art style and music are excellent but the controls and camera angles are frustrating at times. Controlling the boy feels sluggish. The frame rate is also terrible on the Pro. You're lucky if hits 30fps. There are few too many bugs. I've been left floating in mid air, graphics glitching, seen through walls and some puzzles are not triggered when they are supposed to. I've also been stuck where I can not move, forcing me to quit to menu and reload my last save, which there are far and few between. I have had to redo 2 sections of the game which took me 30 minutes to complete.

This game feels unfinished and should never have been released as is. Surely the developers knew about these bugs but they failed to fix them before release. They have announced on twitter that the save points are one of their top priority of things to fix. I just hope they fix all the other bugs too as this could be a great game.

@johncalmc came here to say this. Good job. Lol silly young people lol

@roe Note to self: Good/stylish graphics doesn't equal good game. I thought by this point people would have already learned that but I guess not, and considering that there were other games before Vane that suffered the same issues as Vane, it's pretty clear that everyone will continue to do the same mistakes.

@RBMango They confirmed on reddit that they'll be fixing the game's issues.

Still, the fact that only after the release they are acknowledging the glaring flaws, even after the PSX demo, is unacceptable. YIIK also suffered the same issue.

I like indies but sometimes it makes me wonder if the team even thought of testing the game. It's especially bad when it's a self-published one, so it's not like they were forced to release it before fixing it (something Bandai really loves doing).

Your review has hit this one right on the head! I wish I had a physical copy so I could hit it right on the head with a hammer. Great review should’ve read it before I bought it!

I’m actually starting to change my mind after another session with this. More intrigued by it now rather than frustrated and getting to grips with just being left to your own devices to figure it out!!

@Shigurui Definitely...but I seem to have come across a game breaker though...while playing as the bird I can now no longer call out using the triangle prompt...I land on things that clearly require the assistance of other birds...see the prompt but pressing triangle does nothing!! I can change back to the boy and shout my lungs out using triangle but as soon as I become the bird I’m oddly silent despite the game expecting and requiring me to interact.

Strange!!

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...