Scheduled 60 years in the future where a ruthless corporation and its cyber terrorists hold a city to ransom, EXO pushed the creativity and technological innovation of a Sheffield company to the limit and promised to be a blockbusting, game-changer for the PlayStation 2. Creative supremo Glyn Williams chatted to A Gremlin in the Works author Mark Hardisty about the genesis of Particle Systems, interference from the French, and how his team brought a sprawling metropolis teeming with a squad of mechanical monster athletes to life.

Founded in 1986 by lifelong friends Glyn Williams and Michael Powell, Sheffield-based Particle Systems built a reputation for high quality, cutting-edge simulators such as Subwar 2050 and Warhead. Glyn and Michael came from Britain's long tradition of bedroom coders and had compiled a list of hit games as one-man studios before realising that games were beginning to get too complex for a single person to develop.

After University, Glyn got involved with Island Records whose owner wanted to branch out and follow Virgin into computer games. He set up a company called Solid Image and together with fellow coder Joey Headon created a stylised space crawler, in similar vain to Tau Ceti, called Cholo. "It was based upon an old Philip K Dick book where someone was operating a machine and they are in an underground bunker and the city is on the surface," begins Glyn. "It was wireframe graphics in a tiny little window on the BBC. The guy that did the algorithms is now a cryptographic expert, believe it or not."

His competence with wireframe graphics on Cholo led Williams to be approached to work on the C64 port of Starglider. The approach was made by David Braben's agent and a fundamental relationship began with Jeremy 'Jez' San, and Argonaut Software. After a period freelancing for an American company called Paragon, Williams joined with Powell to create Warhead on the Amiga and ST then Evasive Action for Microprose – their first attempt at a console-style flight simulator.

Their experience on Warhead and subsequently Subwar 2050 inspired greater ambition and desire to create more games in a similar genre. They formed Particle Systems sourcing development talent from the colleges in and around Sheffield. "What I was interested in, and I think Mike too, was making a kick-ass Star Trek," said Glyn. "Star Trek was very politically-correct; how do we keep peace in the world and very utopian. We thought it would be more fun if it was the Warship Enterprise – what would it be like it it was more on a wartime footing."

The resultant Independence War (or i-War for short) was innovative, featuring newtonian physicals for the huge warships and played against a backdrop of conflict between independent pirates and a pseudo Imperial Authority, attempting to dominate the cosmos. The game was taken to Philips Media but in the midst of publication they folded and I-War was passed to Infogrames, who had a stake in the spin-off from the Dutch technology giant.

A sequel soon followed, I-War 2: The Edge of Chaos, again published by Infogrames after Bruno Bonnell dissuaded Williams and Powell to pursue a potential Star Trek: Voyager licence with Virgin Games. "Bruno said we don't want you to go to Virgin, we want you to stay with us and we'll give you a three game deal," clarifies Glyn. The three-game deal secured the immediate future of Particle and cleared the way for the company to begin designing EXO. "We evolved a game narrative that allowed us to do a cool homage to Japanese mecha-stuff, with giant robots and an idea of techno-coolness around everything," beams Williams. "We started with the core conflict which was a highly-mechanised city where something has happened and the robots are terrorising the environment, and they've gone crazy."

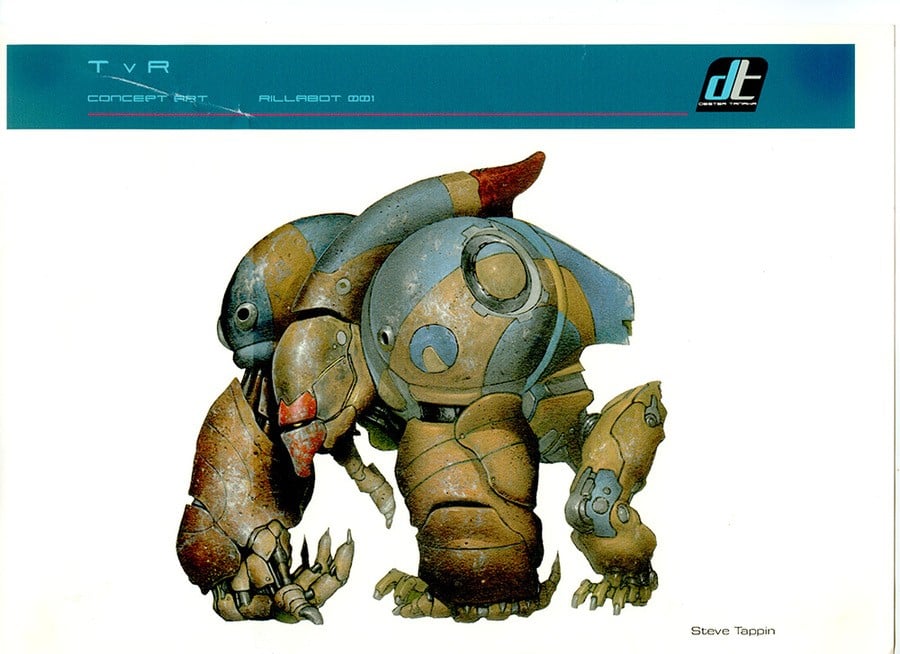

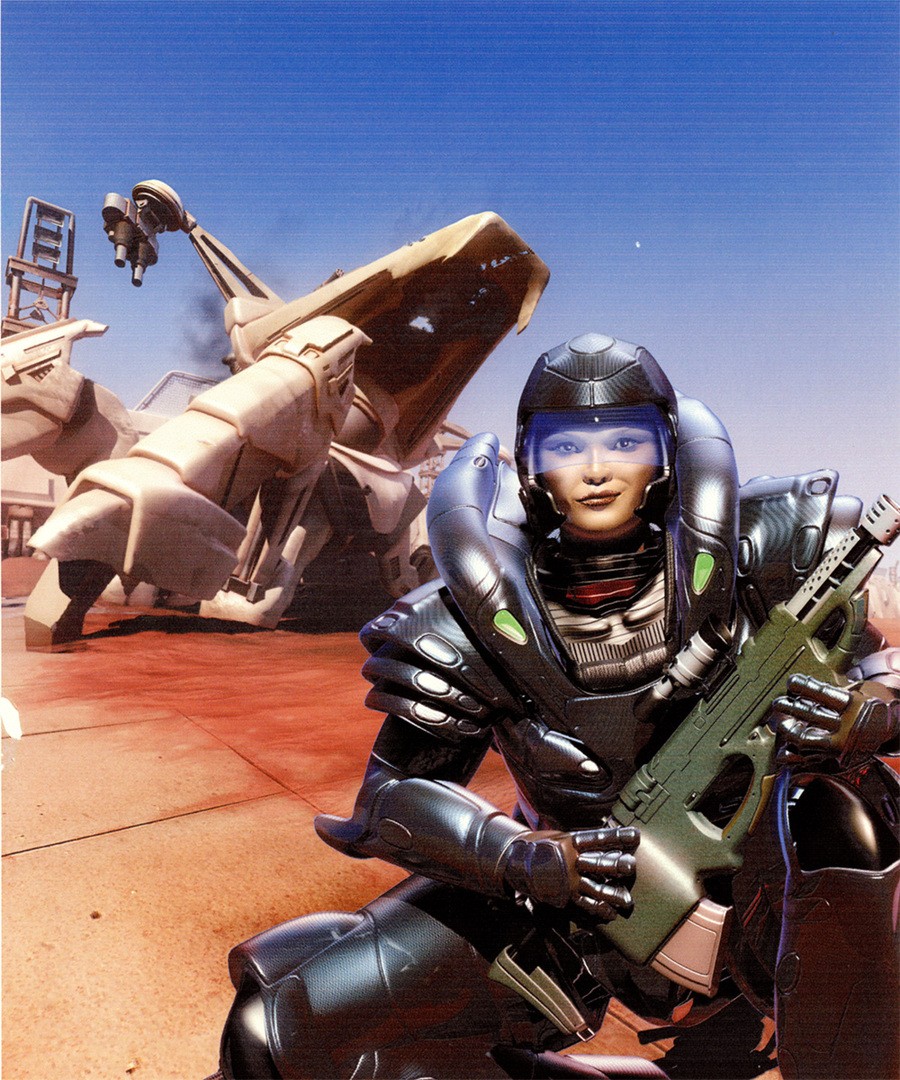

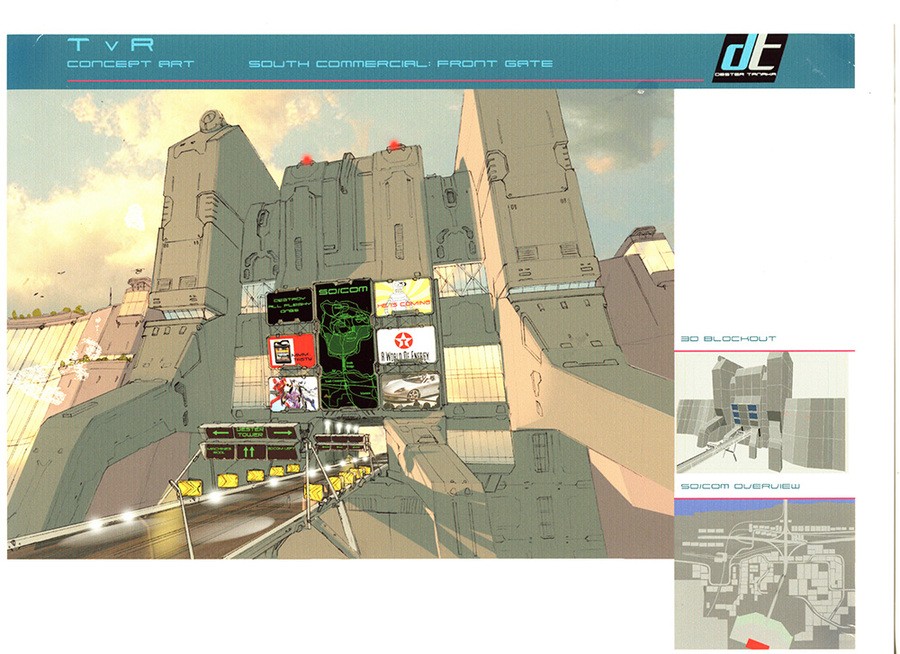

The city in question was 'New Hong Kong', on the northern coast of Australia where the new global superpower, the Chinese, had forced a relocation to a fresh new megalopolis. A rogue organisation, the Dester-Tanaka Corporation, employed a group of cyber-terrorists to subvert the city's networked robotic machines, sending them out of control. Glyn explained the inspirations behind some of the city's mechanised inhabitants: "Robots were animal inspired, quadrupeds – they were a very interesting shape to look at. The idea was to get a T-Rex and cut off its tail and head – it was the T-Mex. We had this core story where someone from the NSA who we thought would be a really cool organisation that would spearhead these kinds of cyber-attacks and guys in power-armour that would be running around the city fighting their way to this central tower."

The attention to detail, and the shear size and mechanical might is plain to see in the game's expansive concept art. There's also a distinct effort to make the game's characters as diverse and empowering as possible – especially in EXO's strong female lead characters ("No obvious breastage," comments Williams). The game's battlegrounds are reminiscent of Blade Runner and Dune and pay homage to Stephen King's Running Man, with large television screens around the cityscape transmitting some automated authoritarian control over the populace. "I don't know if that was an influence," argues Glyn. "We watched everything. Everything is a mash-up. There was all kinds of city environments: there was a level set in the dock, an entrance to the city with a checkpoint, and then you had to work your way towards the central tower. There was an underground reservoir, a power generation plant, and each of them had characteristic look for a particular time of day because it all happened in a 48 hour period."

But how did the game play? According to Williams, it was a hybrid: a cross between first-person perspective, role-playing game, and tower defence. But the decision to make the game based around teams also led to one of the weaknesses in the design, as players controlled a bunch of mechanised "athletes". An admitted mistake looking back. "The problem with EXO," continues Glyn, "and the kindest thing to say, was it was too many windmills to tilt at. It was a shooter in terms of the interface, you would look from a first-person point of view, then you had a multi-character tactical aspect. Most of the problems wouldn't be solved from one character's point of view, but from hopping between members."

This multi-faceted approach needed credible artificial intelligence, something that would keep the player's squad members contributing to the battle, and not being merely passive and getting themselves killed – a trait that appeared in peer games at the time, such as Hidden & Dangerous. The logic was there though, explains Glyn: "We got reasonable behaviour, but it was never finished. We implemented an ordering system so you could defend yourself in a position, or go to this spot, or follow other directives and orders. What we didn't want was to leave a character just standing there with his thumb up his ass and get shot."

As the concept, the narrative, and game logic took shape, Particle's graphic artists and coders attempted to bring to life all of the cool ideas and put them into the EXO digital box. The original design had assumed that the PS2 would be the most amazing hardware of all-time and that anything would be possible. When the development kits arrived in Sheffield, the reality was somewhat different. Aghast, Glyn confesses to a monumental oversight, designing the game's features and specifications without actually having access to any hardware beforehand. "It wasn't apparent that it was a piece of sh*t," he explains. "It was horrible hardware in lots of ways, but I think we over egged the pudding. I put so many [technological] ideas into it, and some of those ideas weren't commonplace until the Xbox 360 era. We had seriously implemented some high-dynamic range lighting which is something you only see in high-end Unreal demos now – where you go outside and there's an exposure shift – we tried that on the PS2! We implemented it by shifting palettes around, so we had to write – this is how silly it was – we had to write our own engine, which at the time was extremely expensive and set back the point at which the game could start to be produced."

The renders that featured everywhere were smoke-and-mirror tricks; combining lower resolution landscape models with super-hi-res lightwave character renders. It did have a sumptuous and minimalistic architectural feel. "We had lots of buildings, lots of architecture," expands Glyn. "Naturalised daylighting, so it had to be light-mapped in which I had to write our own light baking solution because we couldn't find one. I was very interested in this broad illumination thing and [we got it right] by considering every part of the sky as a source of for illumination. When you do that, even plain geometry looks cool."

EXO was previewed to the press at E3, held at Los Angeles in 2001. Infogrames pressed Particle to showcase the game's content but Glyn and team went one better: heading to Canary Wharf (because it was the nearest skyscraper to Sheffield) they mocked up a full digital recreation of the surrounds then had a pair of actors deliver a presentation against a green screen constructed from an office divider and blue sugar-paper. It was designed to make the attendees at E3 believe that they were looking at a live feed from outside of the hall. You can view the video on Glyn's own Vimeo page.

Alongside the gameplay and story progression, the performance under PS2 began to show improvements – but even with the herculean efforts of the Particle team, it still lacked the fluidity required for a console release. It's "photometric" engine began to struggle under the weight of the team's experimentation with illumination and cash was running short forcing Williams and Powell to turn to an old friend, Argonaut Software. "Argonaut had enormous commercial success with their Harry Potter games," outlines Glyn, "and it had a lot of interest so it went public. That meant they had money to burn and they were looking to make acquisitions." Powell purposely courted the sale of Particle in order to keep a suitable level of cash-flow into the studio and ensure its survival. "If Argonaut had not acquired us then EXO would have killed us," states Williams.

Particle was renamed Argonaut Sheffield and apart from the obvious financial benefit, the acquisition also delivered technical serendipity as Argonaut engineers had figured out how to gain extra performance from Sony's new machine. Glyn continues: "A guy called Chris Box who is at Sumo Digital now figured out that the trick was to massage the data to have big rendering structures and leave the processor out of the equation – you stuffed these DMA packets into its rendering chip and it ran on its own, and you could get decent performance given everything."

But it wasn't enough. Time and support from the French wasn't on their side, and without the freedom to rewrite the engine, Particle struggled to match Infogrames' expectations. "I think towards the end we were getting 15-20 frames-per-second and the target was 30. It was a heroic effort by Chris re-optimising and re-optimising just to get where we were. We had permanent crunch time towards the end," said Glyn, who responded to an Infogrames trading update in 2003 that claimed EXO was 95% complete: "We built up an alpha which technically had all of the levels in it. We had quite a pretty thing, some nice designs and a reasonable story, but the gameplay sort of sucked. Gameplay needs to be iterated again and again to be really good. I don't think we ever solved the 'fun' problem."

The publisher eventually ran out of patience. WIlliams estimated that it would be a further year to refine the gameplay to an acceptable point that met his own ambition, which by his own admission was higher than Halo, but with a team-size and budget that wasn't. They couldn't convince Bruno Bonnell and his cohorts to move the game to the Xbox and provide the funds to match the platform. Infogrames seemed to be supporting a lesser product, Outcast instead of EXO. Funding was cancelled.

Once EXO had been cancelled, Sheffield provided several licensing pitches for Argonaut based upon several IPs that were available at the time: Zorro – in which Williams and Powell married a Batman theme with the movie – Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and a Han Solo standalone game: "For some reason somebody also thought a young Han Solo standalone project would be really good, and now they're talking about doing a standalone movie!"

In retrospective Glyn is proud of what his team achieved, especially in the production of the narrative and concept artwork: "We ended up with some world class stuff. If I'm proud of anything, I'm proud of this – I've seen feature films that aren't even to this quality." And did he have any regrets over never completing his masterpiece? "To be frank, I saw it as a failure. I failed. If we'd have been backed by an incredibly wealthy American publisher who had a bit more nerve and who would have invested a bit more and seen it through – but Infogrames didn't want to be that for a perfectly good reason."

After EXO, Particle's future was shaped by its owner, Argonaut. Instead of allowing the maverick studio to concentrate on "crazy 3D and futuristic sci-fi stuff" it kept with the licensing business model after the success of Harry Potter. Particle supported the development of I-Ninja and Catwoman – a "folly" according to Williams, that along with Malice burned through its parent's cash reserves. Argonaut ran out of money in 2004 and closed all of its studios (Sheffield in October 2004) apart from Ninja Theory, whose Heavenly Sword title was perceived by Sony as a viable product.

Glyn has no regrets, though, stating: "I couldn't wish for a better thing to work with people who were genuinely talented, often more talented than one's self and that's an enormous privilege."

Mark Hardisty is the author behind A Gremlin in the Works, a lavish 572 page book documenting the uprising of Sheffield-based video game institution Gremlin Graphics. The book includes interviews with key team members, as well as never before seen imagery, spanning everything from concept art all the way through to business cards. You can purchase the book through here.

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.

Comments 6

A really interesting story, I enjoyed reading this.

I always love these pieces, give us an inside look into the industry and I appreciate them. Great read.

A shame, it sounded like it could have been a good Sci-fi game and had some cracking influences. Which reminds me, I must go back and play Remember Me sometime.

Enjoyable read but calling Outcast a lesser game?

Always enjoy articles like this which uncover a bit of gaming history. Thanks for putting it up!

Great read and great article. What might have been stories are just fascinating.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...